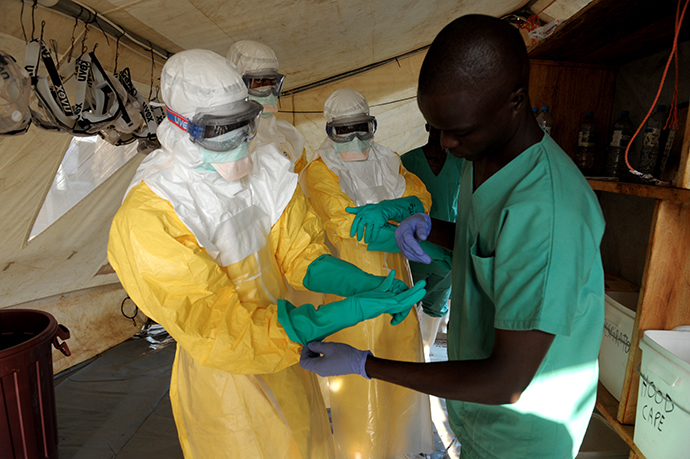

Biosafety experts fear U.S. hospitals may be unprepared to properly dispose of the infectious waste produced by any Ebola virus disease patient to arrive unannounced in the country, which could potentially put the entire community at risk.

Reuters reports that waste management companies are refusing to remove the linens and protective gear spattered with the fluids of infected patients, citing federal guidelines that require Ebola-related waste to dealt with in special packaging by people with hazardous materials training.

However, many U.S. hospitals are unaware of this regulation, which could possibly threaten their ability to treat any person who develops Ebola in the U.S. after coming from an infected region.

Experts fear such a situation is likely, as the CDC reports that up to 1.4 million people could be infected with the disease by mid-January in the Western African countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Experts say it is only a matter of time before at least some infected patients are diagnosed in U.S. hospitals, most likely walking into the emergency department seeking treatment.

The issue of waste is also not foreign to hospitals within the U.S.; when Emory University Hospital in Atlanta was treating two U.S. missionaries who were evacuated from West Africa in August, their waste hauler, Stericycle, initially refused to handle it.

"At its peak, we were up to 40 bags a day of medical waste, which took a huge tax on our waste management system," Emory's Dr. Aneesh Mehta told colleagues at a medical meeting earlier this month.

To deal with the issue, Emory sent staff to Home Depot to buy dozens of 32-gallon rubber waste containers with lids, which the hospital kept in a special containment area for six days until the CDC helped create an agreement with Stericycle.

"Our waste management obstacles and the logistics we had to put in place were amazing," Patricia Olinger, director of environmental health and safety at Emory, said in an interview.

Another part of Emory's solution was to bring in one of the university's large-capacity sterilizers called an autoclave, which uses pressurized steam to neutralize infectious agents, before handing the waste off to its disposal contractor for incineration.

Unfortunately, few hospitals have the ability to autoclave medical waste from Ebola patients on site.

"For this reason, it would be very difficult for a hospital to agree to care for Ebola cases - this desperately needs a fix," said Dr Jeffrey Duchin, chair of the Infectious Diseases Society of America's Public Health Committee.

Dr Gavin Macgregor-Skinner, an expert on public health preparedness at Pennsylvania State University, said there's "no way in the world" that US hospitals are ready to treat patients with highly infectious diseases like Ebola.

"Where they come undone every time is the management of their liquid and solid waste," said Macgregor-Skinner, who recently trained healthcare workers in Nigeria on behalf of the Elizabeth R Griffin Research Foundation.

The CDC is reportedly working with to resolve the issue, says Skinner, adding that the CDC views its disposal guidelines as appropriate, and that they have been proven to prevent infection in the handling of waste from HIV, hepatitis, and tuberculosis patients.